Beauty and the Yeast

Had it not been for the yeast, we wouldn’t have any wine at all.

Invisible to our naked eyes, yeast works quietly in turning the sugar in the grape juice into alcohol and energy. The action is only noticeable by the carbon dioxide released in the form of bubbles from the fermenting juice.

This is how you can see yeast working.

There are many species of yeast. Over a significant part of the history of winemaking, fermentations were carried out using whatever yeast happened to be in the grapes - wild yeast, mostly commonly Kloeckera/Hanseniaspora, Candida and Metschnikowia. They start off the alcoholic fermentation unless they are killed off by sulfur dioxide. They are the soul of the wild fermentation as these species produce interesting flavour compounds and texture. However, they cannot tolerate high alcohol level and will die off when the wine reaches 4% alcohol level. Then another species Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is higher alcohol tolerant takes charge and finishes off the fermentation process.

Wild yeast fermentation is said to produce a more complex wine because more yeast species are involved in the process, hence more chemical reactions have occurred, and thus more flavour and aromas compounds have been produced. These wines are also regarded as more expressive of terroir as they are fermented by yeast species present in the vineyard, clinging to the winery walls, sticking to equipment, lodging in the wood grain of barrels, and becoming unique to each locale – indigenous yeasts are part of the character of the wine.

Wines are bottled together with the characters coming from the climate, soil, grapes and ambient yeasts living around the vineyard and the winery.

It was until 1960s when scientists found a way to isolate and commercially produce cultures of selected strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which winemakers prefer for their specific attributes based on the wine style required. Wines produced by inoculated yeast strains are more reliable, consistent and easy to control; if you are producing large quantities of wine (which most winemakers are), this is a safer approach. This helped the development of the New World wine industry in the 19th century especially when there was a favour for clean, attractive fruity wines produced in a large industrial scale for which winemakers needed a much surer route to this goal than relying on what’s on the grapes alone.

But human’s wine taste preferences, like those for fashion and music, change from time to time. Just as we have unplugged music, ’Natural wine’ has been one of the major movements of the 21st Century wine world, some indigenous yeasts are “bad” and can result in spoilage; even “good” yeasts can pose a challenge as they don’t always achieve enough alcohol content; this process takes longer, so the winemaker needs to watch out for spoilage via oxidisation; wild ferment is riskier and creates less reliable wines which can be off in aroma/taste. On the other hand, inoculated yeasts are not ’unnatural” at all, they are isolated and cultured natural yeasts. Organic and biodynamic producers leave fermentation to indigenous yeasts, not because there is anything non-organic about cultured yeasts, but because they believe that relying on cultured yeast leads to homogenisation of wine flavours.

Thanks to my friend Tony Ling, I have tried some good quality ‘drinkable’ natural wines in a “Sauvage Wine” event! Natural wines do not necessarily taste like vinegar; they do not necessarily have a cloudy appearance too. Most of them are much less fruity and much more yeasty in their aroma profile than a typical wine, some topped with interesting spicy kicks, some with subtle savoury, earthy nuances - they were, just as being introduced in the flyer, a little fun, a little serious and a little weird (but in a positive way)!

Wines tasted at “Sauvage Wine” event. Sauvage is French meaning natural or wild.

Earlier this week, in a wine dinner hosted by Burn Cottage from New Zealand which upholds minimal intervention winemaking, I have had a vertical tasting of their Pinot Noir which they had minimal sulfur usage and avoided all additives whenever possible, e.g. use of cultured yeasts, bacteria, associated nutrient products and filters. I can sense on top of the beautiful fruit given by the sunny weather of Central Otago, and there are subtle layers of yeastiness and spiciness. They are there!

Burn Cottage’s unique Riesling-Gruner Veltliner blend expresses succulent citrus and floral fruit along with herbs, white pepper, mineral and nutty flavours of a fine, textural plate with freshness and presence.

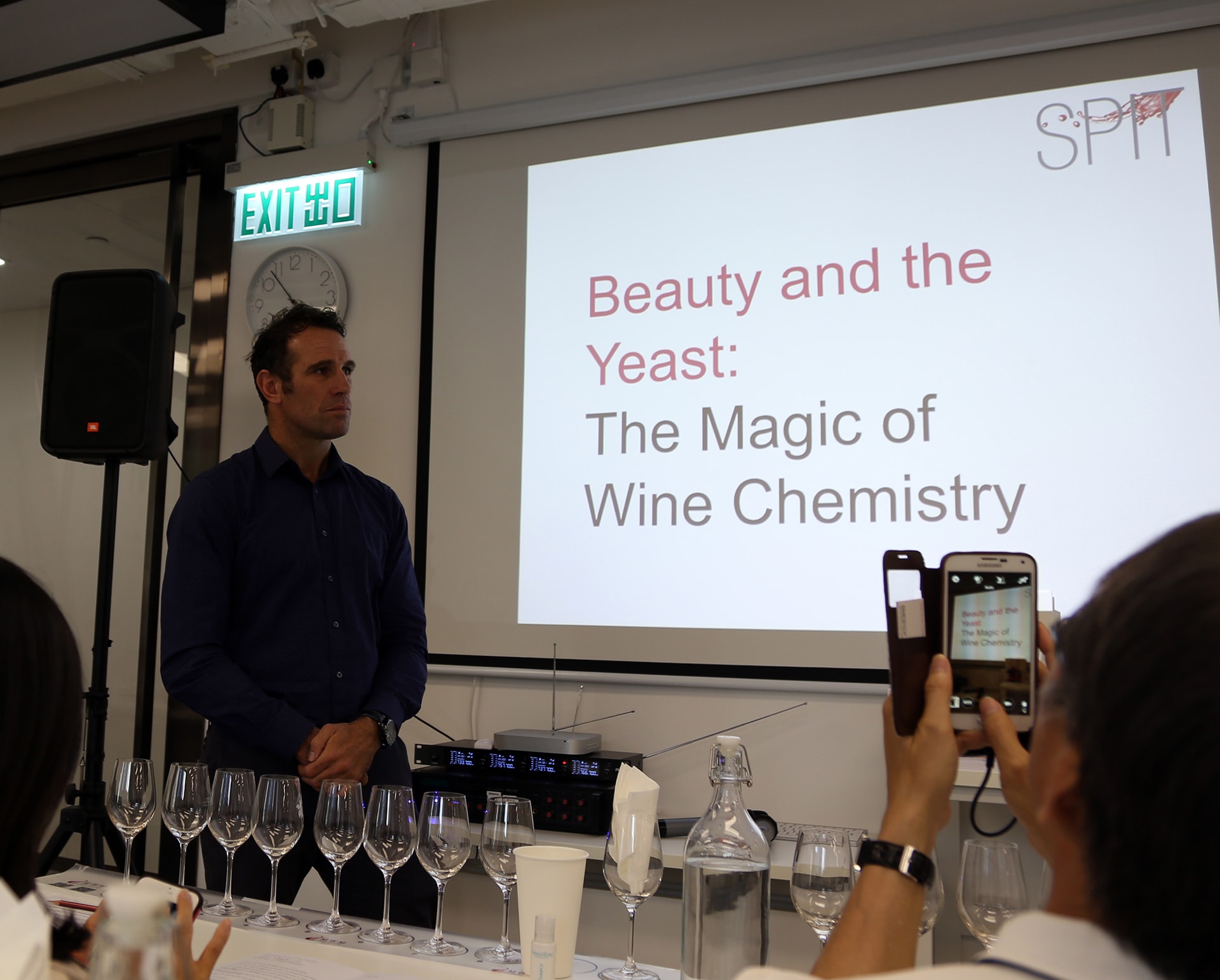

Given the risk of wild yeast fermentation, how could those Old World traditionalists and the New World natural wine proponents make it? In a recent WineSPIT workshop themed “Beauty and the Yeast”, the guest speaker Jeremy McKenzie, Chief Winemaker of Isabel Estate from Marlborough, New Zealand explained to us. The winemaker picks a small portion of their grapes a week before the harvest. At this point, the pre-harvest grapes may still be acidic. If so, water is sometimes added, and the grape juice is stirred and aerated to stimulate the wild yeast and get it fermenting. After several days, the pre-harvest grapes will be fermenting vigorously as a yeast starter. This starter culture (French: Pied de Cuve) is used to inoculate the harvested grapes as they come in from the vineyard. In a way, the grape juice is inoculated with wild yeast. Genius!

Jeremy McKenzie, Chief Winemaker of Isabel Estate from Marlborough, New Zealand

Wines tasted at WineSPIT workshop “Beauty and the Yeast”

Article by: Philip WONG, DipWSET

References:

- Jamie Goodie, “Wild Fermentation Is the Sexiest, Least Understood Technique in Winemaking”, February 26, 2018

- Jeff Chorniak,, “Wild Yeast: The Pros and Cons of Spontaneous Fermentation”, Jeff Chorniak, October/November 2005

- Jill Haapaniemi, “What is Wild Yeast Fermentation in Wine?”, Wine Compass Blog

© 2024 Vinetude - All Right Reserved