TEMPRANILLO VS. TEMPRANILLO

(Part I)

Or to be exact, Tempranillo vs. Tinto Fino vs. Tinta de Toro.

Tempranillo is the “king” in Spain. Since the beginning of this century, Tempranillo has overtaken other varieties, such as Garnacha and Bobal, as the most popular red in Spain. Yet, just because it is grown in almost every region of the country (except in the far South and Northwest), Tempranillo is hardly a one-size-fits-all grape variety. Spain, as a nation, is extremely heterogeneous and encompasses multiple cultures and religions. Its language base is enormously diverse, covering 6 main official/co-official languages – Castilian, Euskera (Basque), Catalan, Gallego, Valencian, and Aranés – plus many others. Gastronomy varies greatly from Andalusia to Castile-La Mancha to Catalunya. Some even half-jokingly said that the only thing that unites the country is football. As such, viticulture and vinification are no exceptions.

Whether it is called Tempranillo (Rioja), Cencibel (Valdepeñas), Ull de Llebre (Penedès), Tinto Fino /Tinta del Pais (Ribera del Duero), or Tinta de Toro, the grape usually carries characters of strawberry, spice, savory notes (leather, tobacco leaves) and medium-to-low acidity. So how does one differentiate the various styles of Tempranillo among the vast planting of 206,000 hectares (as of 2011) within Spain? In Oxford Companion to Wine, Tinto Fino from Ribera del Duero was quoted as producing “deep-colored, occasionally astringent, firm-flavored red wines”. Wine Folly describes the ones from the Duero Valley collectively as “typically deeper, darker, and more brooding”, and with “more blackberry fruit flavors and intense, gripping tannins” than those from Rioja. Whereas Rioja leads the country in Tempranillo planting by area, Ribera del Duero, which includes Bodegas Vega Sicilia and Dominio de Pingus, claims the crown equivalent of the First Growth status.

With this “textbook definition” of Tempranillo in the back of my mind, I set out my expedition this summer to Spain to see the land and meet with the winemakers who yield the “red fruit” characters in Rioja, “blackberry” notes in Ribera del Duero, and “gripping tannin” in Toro. I deliberately started my trip in Rioja so that I could first experiment Tempranillo in its most classic presentation, followed by Ribera del Duero for its premium style, and finally to Toro the newcomer for a twist.

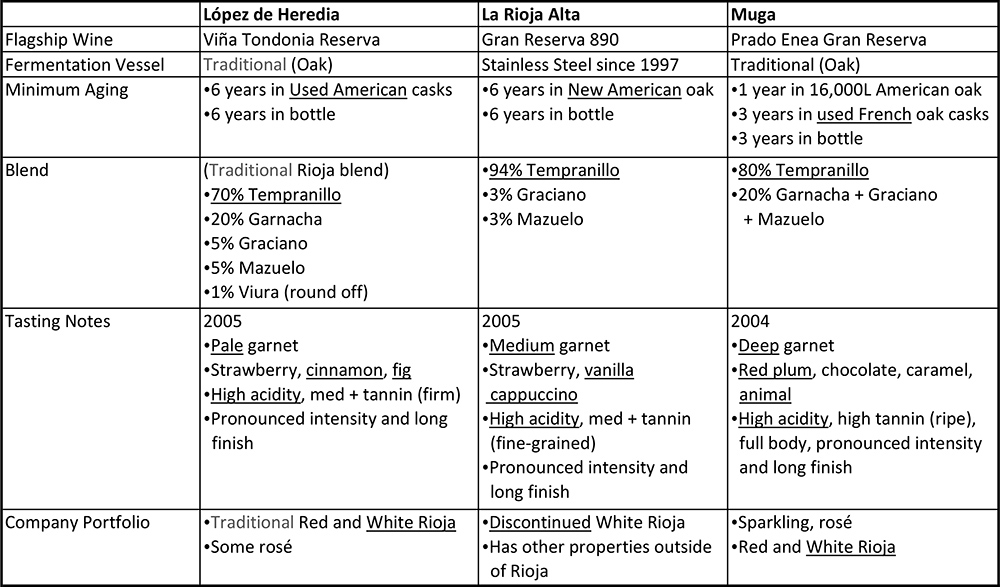

Benefited from the misfortunes of powdery mildew and phylloxera in Bordeaux in the mid-19th century, Rioja was the first region in Spain to adopt French winemaking technologies. The bodegas I visited – López de Heredia Viña Tondonia, La Rioja Alta, and Muga – are neighbors literally on the same street, all next to Haro train station. Regarded as part of the “traditional stream”, they are also the “three remaining bodegas in Rioja which have upheld the tradition of using their own cooperies for their barrels. Think I would see wines very similar in style? See below for the comparison of their flagship wines:

It is interesting to see the variations in their methodologies and expressions. López de Heredia Viña Tondonia is considered to be the most traditional of all. Most wineries in the region have stopped producing a white Rioja, but López de Heredia persisted to make the wine the way they always had (85% Viura and 15% Malvasia with 6 years in barrel). The regulation of Rioja DOCa allows 15% of blending from the previous year, and they have been following it. Inside the bodega, temperature and humidity were regulated by utilizing an underground system, their famous “mold”, and the nearby river. They even continued to pay their harvesters by the weight of each basket (piecework system) like they did a century ago. But wouldn’t “old-school” customs become outdated one day? Not necessarily. In fact, Don Rafael López de Heredia, the founder, was quite a visionary. Generations ago, the family purchased land surrounding their vineyards for agriculture (potatoes, tomatoes, etc.) so that they did not have to worry about contamination by outsiders. As we now know it, this practice is one of the fundamentals of modern biodynamism. Their payment method for their harvest workers, I would even argue, is a principle from MBA 101: pay-for-performance. As for their wines, I do not think they have ever fallen out-of-fashion. Sure, their Viña Tondonia Reserva is the most restrained of the three wines above, but its subtlety and lingering finish just made me want to have some more. Loyalty to tradition should not be viewed as stubbornness, but a manifestation of confidence and passion instead. And in some cases, sticking around long enough while others quit somehow turns you to be a pioneer one day.

On the other hand, La Rioja Alta has made some adaptations over the years. For example, the decision to switch to 100% stainless steel fermentation starting in 1997 was to ensure proper temperature control and quality of their wines. The dramatic increase in the size of the export markets (15% before the financial crisis compared to 50% after) also has an impact on their style and allocation. One important element that has not changed was their insistence on extended aging of their Gran Reserva 890 prior to release. The special wine is declared about 3 vintages a decade, and aged for at least 12 years (6 years in barrel and then 6 more years in bottle). This led to a massive 8 million bottles in their cellar, which makes storage a complicated matter. Racking the wine about every 6 months for 6 years also means losing approximately 6L of wine per barrel.

But all these pay off. La Rioja Alta Gran Reserva 890 was elegant and sophisticated. The influence of new oak (vanilla) was apparent, but it was harmonious and added dimension to the wine. The much higher percentage of Tempranillo in the blend also provides vibrancy to balance the effect of new oak. While the early-drinking Viña Alberdi is the winery’s bread and butter, the patience to age Gran Reserva 890 properly is essential for this superstar.

Finally, the style of Muga was comparatively the most modern of all. Being the youngest of the three (“only” 86 years of age), Muga seemed to be the most adventurous and has developed the largest selection of Rioja wines in this group (2 sparklings, 2 rosés, 1 white, and 5 reds). I had tasted all of their Prado Enea, which is only produced in the best years, from the last decade. The vineyards for Prado Enea are at an altitude of 600 meters. Therefore, even though the wine was full-bodied and had pronounced flavors of coffee, chocolate, and dried fruits, the high acidity and ripe tannin kept the structure very controlled. Another wine of interest is their Torre Muga, a wine made in a more contemporary approach and spent at least 18 months in new French oak casks. The family wanted to make a wine reflective of local life and palate, and Torre Muga certainly complements regional dishes of Rioja, such as lamb stews. While Prado Enea might suit the international customers, Torre Muga is more for home. I am always impressed whenever I see winemakers pay a special tribute to their roots.

As I left Rioja and headed to my next stop, I couldn’t stop thinking how Tempranillo already presents quite differently along one short block of Avenida de Vizcaya. Let’s see what I’ll get in Duero Valley.

(To be continued)

Article by: Alice WONG, DipWSET

© 2024 Vinetude - All Right Reserved