TEMPRANILLO VS. TEMPRANILLO

(Part II: Ribera del Duero y Toro)

Traveling approximately 200 km southwest from Rioja would take you to Valladolid, the main city for the Duero Valley. As a reference point, Ribera del Duero DO is about 40 km east of Valladolid, while Toro DO is approximately 90 km to the southwest. The climate at the Duero Valley is continental, compared to maritime-continental Rioja Alta. When we arrived the area at 3 pm, we could not help but put on all our UV-protection gear against the blazing sun. But by 10 pm, temperature fell sharply and became cool and pleasant (esp. to the grapes). Through conversations with winemakers later in our trip, we learned that local residents only get to enjoy this summer weather, albeit as hot as 40oC, for about 3-4 months a year. Thereafter, daytime becomes shorter, making it an important factor for vineyards with the best exposures to capture more sunshine before harvest. By November, most wineries are prepared for the harsh winter, typical of a continental climate.

Climate is not the only aspect that distinguishes the Duero Valley from Rioja. Ribera del Duero is a younger Demoninación de Origen (DO), formed in 1982. Its total planting area was 21,500 hectares (as of 2012), which was only 1/3 the size of Rioja. Business establishments are not as developed as those in Rioja, where most wineries have their own tasting rooms and tour programs. At the Duero Valley, wine tourism is still exploring its way. In fact, two of the most famous winery, Vega-Sicilia and Dominio de Pingus are generally not open to public visit. So, how did Ribera del Duero, with a shorter history and much smaller production volume, rise to international fame and rival blue ribbon Rioja? What were the factors that drew their wines apart?

The first stop of my exploration was Vega-Sicilia, regarded by many as the most prestigious winery of Spain. Its home on Valbuena de Duero is nothing less than grandiose, and our reception at the winery was marked by sophistication. After we passed the security gate, we toured around their winery and the Japanese garden, tasted their wines at the Alvarez family house, before we checked out their vineyards on the south bank of River Duero.

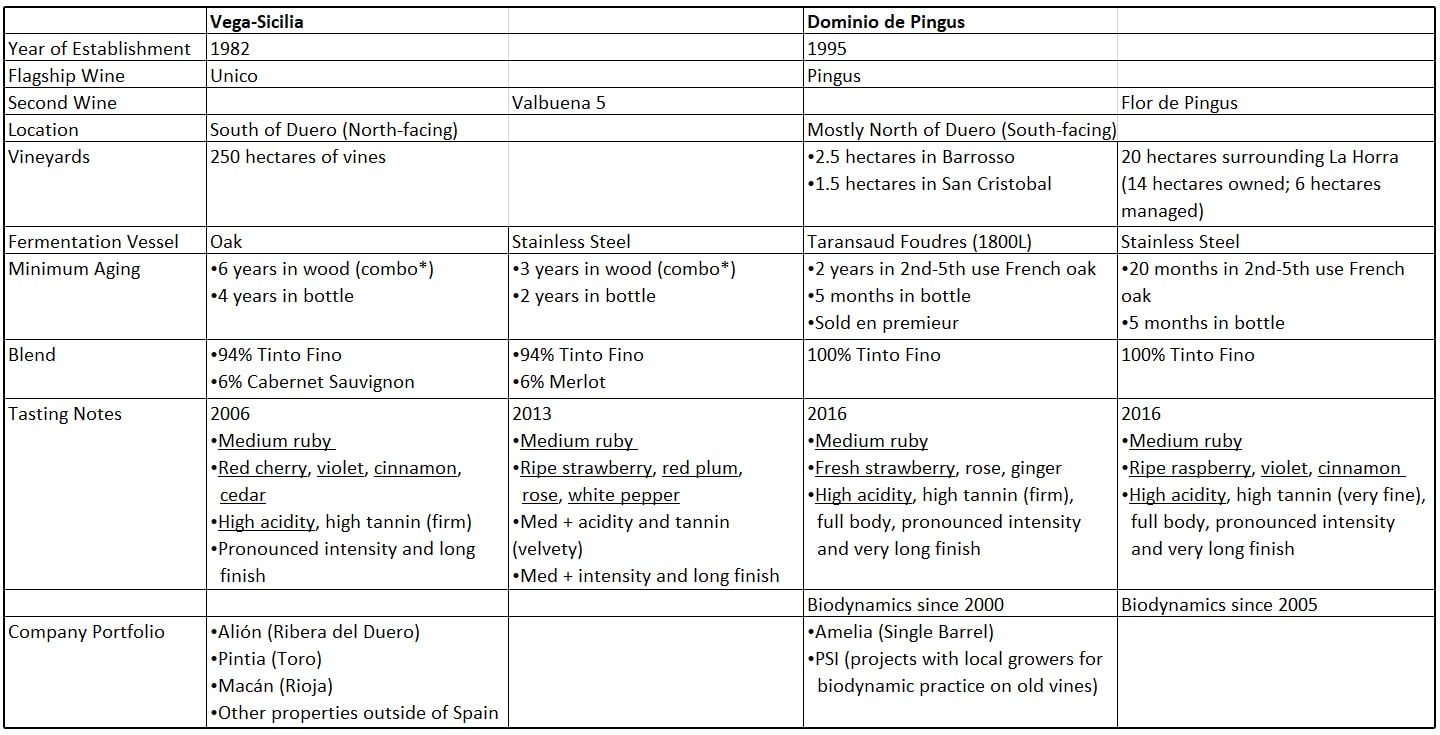

The estate has about 1000 hectares, but only 250 hectares were planted with vines. Boasting a variety of 19 types of soils, the vineyards were divided into 52 plots since 2001, with their grapes fermented separately. For Vega-Sicilia, part of their success lies on their willingness to explore and their strive for excellence. The best illustration is their wood maturation program. Both their Unico and Valbuena 5o are aged in a combination of French and American oak, new and used 225L barrels, 20,000L vats, and for various duration. The wines are racked into a different barrel every 5 months to obtain the optimal integration. There is no exact formula on how they proceed with these combinations; every barrel is tasted meticulously to come up with the best result based on a particular vintage and plot. To achieve their desired level of precision, they tested but ultimately rejected the use of visual technology for grape selection and continued with traditional manual triage. Valbuena 5o is aged for 3 years in wood and 2 years in bottle, making a total of 5 years prior to release, hence the number “5” in its name. Its high proportion of Tinto Fino (>90%) and small contribution of Merlot gave me the impression of rose, ripe strawberry, red plum, velvety tannin, and a bit of spiciness (white pepper and licorice). Their flagship, Unico, has a similar proportion of Tinto Fino, but is blended with Cabernet Sauvignon instead. Its aging is doubled, with a minimum of 6 years in wood and 4 years in bottle. Unico definitely has a stronger backbone, but very fine-grained tannin, carrying nose of cedar, violet, cinnamon, red and black cherries, and wet leaves. The 2006 Unico that we tasted was also recently given 100 points by James Suckling. How lucky were we!

Compared with the enormous empire of Vega-Sicilia, which also owns other wineries outside of Ribera del Duero and Spain, Dominio de Pingus is the iconic cult winery of Spain with a stark contrast in size. Sitting quietly at the little town of Quintanilla de Onésimo, the white-colored house of Pingus is so low-keyed that we would have missed it had we not received pictures from the winery beforehand. Hidden within these walls is a cellar discovered in the 1830s and was believed to be one of the oldest in the area. With no intention to grow beyond what they are today, the boutique winery was compact, housing basically everything they need and nothing more: 16 stainless steel tanks for Flor de Pingus facing 5 Taransaud Foudres for Pingus. But the dream of founder Peter Sisseck goes beyond this premise. What captured his heart and started the legend of Pingus in the early 1990s were the old vines of Tinta del Pais in the La Horra region – a relatively minute 4.2 hectares of 80 year-old vines for Pingus, later on extending another 20 hectares of 60 year-olds for Flor. Determined to stay true to this terroir of 800 m altitude, Sisseck took utmost care of his land and protected the present and future of its roots according to the smallest details. Practicing biodynamics since 2000 for Pingus and 2005 for Flor, the estate will soon have their own cows producing manure. Yield is extremely low for Pingus, sitting around 12 hectoliters/hectare and producing fewer than 500 cases annually, while Flor can reach about 4000 cases. In 2007, the winery built its own laboratory to run monthly analysis. When it comes to winemaking, the winery applies the rule of “minimal intervention”. Natural yeasts are employed for fermentation, and egg whites are used only as needed for filtration. Aging is also relatively simple, employing 2nd to 5th use French oak from 2 suppliers. Pingus is usually aged in oak for just 2 years, and even shorter for Flor. The wines are then laid in bottles for a minimum of 5 months before they are shipped to allocation, as everything is sold en premieur. The wines I tasted on that day – from 2016 and 2017 – were the youngest wines I tasted in my trip. Flor was very floral on the nose, with ginger and loads of fresh strawberry lingering. Pingus had riper raspberry characters, but balanced very well by touches of violet and cinnamon. For the Pingus, everything seemed “just right”. The fruit and spicy notes were pronounced, dwelled on, but at the same time ultra clean. I believe this is what some wine critics called “laser-cut precision”.

As I put the specs of these 4 wines side by side, the first thing I noticed was the higher percentage (94-100%) of Tinto Fino for the wines in Ribera del Duero, compared to the 70-94% of Tempranillo for those in Rioja. So what happened to the “deeper, darker” notes I kept looking for? Not consistently found. Instead, floral notes and sweet spice seemed to be the theme. Valbuena 5o and Flor, the 2nd wines of both wineries, were particularly feminine. I checked on my biodynamics lunar calendar – those were “fruit days”, not even “flower days”. Could that have made a difference? Or, maybe it is their diligence in the vineyard and supreme technical refinement in winemaking that shock us with the beauty of Tinto Fino we have not seen before?

My final destination, Toro DO, was formed in 1983, and only had a dozen of bodegas 20 years ago. Today, that number rose to 63. Bodega Numanthia is one of the few “long-timers” who set foot at Toro before the turn of this century. Currently owned by LVMH, Numanthia has about 90 hectares of Tinta de Toro and 3 hectares of Verdejo. The name “Numanthia” came from a local town that was, in the ancient times, surrounded by the Romans. Refusing to surrender at the end of their 20-year battle, these locals chose to kill themselves. The original owner of this bodega chose this name to draw the parallels between the fighting mentality of the people here and the resilience of their vines. Growing in a tough environment where average annual rainfall is only about 300mm and irrigation is prohibited, the roots of these Toro vines go deep to 20 feet to fight survival. With summer temperature reaching up to 35oC, altitude is key to offset the heat, and some vineyards are planted at 700M. Numanthia is especially blessed as they have a high percentage of phylloxera-free, ungrafted vines that are organically farmed. Their love for this land is further proven by the way they preserve these high-maintenance bush vines. Their oldest vines aged 100-130 years and are destined for their flagship wine, Termanthia, while the 50 year-old vines go to their 2nd wine, Numanthia. To honor traditions, the grapes for Termanthia are crushed by foot treading. After 1 week of alcoholic fermentation in stainless steel tanks, the wines are left for maceration and malolactic fermentation for a total of 4 weeks. The “roughness” of these 100% Tinta de Toro wines are then mellowed by 18-20 months of aging in 100% new French oak, and a further 2-2.5 years in bottles. I had a vertical tasting of Termanthia from 2006-2010. Most of these wines are indeed deep-colored, powerful, slightly grippy, and full of black currant and black cherry tones. I did not find them aggressive though, as the oak and alcohol were all well-integrated, giving notes of caramel and toast. As I looked out from the tasting room, all I could do was to admire how these centennial vines withstand this challenging climate and reward the people who put in hard work and turn them into outstanding wines.

Of all the “noble grapes”, there are no other ones like Tempranillo (perhaps other than Sangiovese), so original to one country, yet with so many expressions in different parts of that country. There is no “Tempranillo for Dummies”, as the style of Tempranillo also differs at the winemaker’s discretion. The blueberry tone of Torre Muga from Rioja is a perfect match with local food and sauces, almost fooled me as Tinto Fino. On the contrary, are the sweet, floral notes of Pingus a fair representation of the black-fruit-dominant Ribera del Duero? Maybe not. But it reflects what Peter Sisseck perceives, and shocks us with the beauty and elegance of Tinto Fino we do not usually see. As for Toro, the youngest DO of the 3 actually has some of the strictest regulations, such as manual harvest, prohibition of irrigation, and the use of 100% Tinta de Toro in all levels of DO red wines (except for “Tinto Roble”). Perhaps it is the intention of the DO to highlight the power and concentration of this grape on their turf. And why not? Beauty is in the eyes of the beholder. Diversity is in the blood of the Spaniards. Tempranillo is simply as intricate as its native land is!

(The End)

Article by: Alice WONG, DipWSET

© 2024 Vinetude - All Right Reserved